Pololu Blog »

Posts tagged “open-source hardware”

You are currently viewing a selection of posts from the Pololu Blog. You can also view all the posts.

Popular tags: community projects new products raspberry pi arduino more…

Starlite by Grant Grummer

Grant Grummer used our laser cutting service to create 6- and 8-point acrylic stars for his project, Starlite: A programmable star-shaped canvas for displaying light patterns.

Starlite uses a 3mm thick laser-cut piece of translucent white acrylic (#7328 white, also called “sign white”) for the front face. The LEDs mount onto a thinner (1.5mm thick) piece that has rectangular cutouts that allow the LEDs to connect to the controls, the main control board, and an UPduino daughter board.

You can read more about Starlite on Grant’s Make: Projects and GitHub pages.

If you are interested in making a similar light display, be sure to check out our selection of LED strips!

PULSE: A pendant to warn you when you touch your face

|

PULSE pendant by JPL. |

|---|

PULSE is a 3D-printed wearable device designed by JPL that vibrates when a person’s hand is nearing their face. It’s based around our 38 kHz IR Proximity Sensor, and was designed to be relatively easy to reproduce (it doesn’t require a microcontroller or programming, but you do need access to a 3D printer to make the case). The project is open-source hardware, with complete instructions, design files, and a full parts list available on GitHub.

These are the parts that can be purchased from Pololu:

- Pololu 38 kHz IR Proximity Sensor, Fixed Gain, High Brightness

- 10×2.0mm or 10×3.4mm shaftless vibration motor

- Mini Slide Switch: 3-Pin, SPDT, 0.3A

- Wire

Here’s a short demo of our intern Curtis using a PULSE pendant he made himself:

You can find more information about the PULSE pendant on the PULSE website.

Rethinking open source in the context of the coronavirus pandemic

We are into week 6 of emergency operations. Our day-to-day routines are largely unchanged from what they were last week (we continue to ship all orders on time with a reduced on-site staff), so please see my earlier posts for more details about that. After more than a month of a new normal setting in, we are striving for a balance of avoiding complacency in daily operations while planning for a future that will likely never be back to how things were a few months ago.

One of our team members passed away (probably not directly related to the coronavirus)

On the complacency front, we were reminded of the stakes when one of our employees unexpectedly passed away at the end of last week from a sudden illness that, from the limited information we have available, was not related to the coronavirus. She was not part of our reduced, on-site staff, so I last saw her in person six weeks ago, and she was in contact a few weeks ago. As the toll of the pandemic mounts, more and more of us are going to be hit increasingly personally, from losing jobs and businesses to missing out on pivotal moments like being present at a child’s birth, to literally life and death experiences made even more painful by new restrictions on being with loved ones and being able to mourn.

However things play out and however bad they get, let’s try to be part of making things better. We can be responsible, supportive, useful, thoughtful, helpful. Many of us are suffering, and probably the only ones not afraid are the ones too unaware to know they should feel some fear. But we can acknowledge the fear without letting it completely overpower us, and we can still look for places in our lives where we can make a difference and decide to make things better.

Rethinking open source in the context of the coronavirus pandemic

|

The rest of this post is about a longer-term strategy I am thinking about in response to the pandemic: moving toward more open-source projects (both for software and hardware). I would very much appreciate any thoughts and advice people have on the subject.

I wrote about open-source hardware exactly eight years ago this week. I just read it for the first time in maybe five years, and although I feel like I could have written the same thing recently, in many ways I’m a different person than I was then, with the usual progress one would hope for from living another 25% longer, supplemented with extra jolts to my system from things like my baby dying the day before he was born over five years ago and the coronavirus pandemic we have all been shocked by this year. It took me most of those five years to really be able to move on from Dez dying, and when I was locking up Pololu on the Friday a month ago after the first week of escalating government-mandated shutdowns, I really thought I might not be reopening it for weeks and that there would be little chance of Pololu surviving.

Having weathered the past five weeks of emergency operations and being one of the lucky businesses to get temporary funding via the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP loan), my outlook about Pololu making it has substantially improved, and with solvency likely assured for at least a few months, I am thinking about strategic changes for medium and long-term survival in a very different world where the future looks especially uncertain. Here are some of the changes to the world and to Pololu that make open-source projects much more compelling than eight years ago:

Longer-term changes preceding the coronavirus pandemic:

|

Laser cutting Zumo blades at Pololu on 22 April 2020. |

|---|

- Pololu’s manufacturing capabilities and sophistication have improved substantially over the past 8 years. (I still believe that open-source hardware makes more business sense for those with manufacturing capability since competitive advantages would move from product design to production capability, which is more difficult to copy.)

- Copies of our products and documentation and other IP have become a big problem. Even in cases where there might not have been outright fraud intended (e.g. counterfeits being falsely sold as products made by Pololu), consumers of knock-offs take up our support staff time, introduce confusion and uncertainty among customers who have genuine versions of our products, and generally dilute the value of our brand. At least for some products, it might be more pragmatic to officially open up the designs than to fight the copies.

- Our brand and processes and relationships (e.g. with our distributors) and other aspects of being a successful business have grown. This gives us value and competence beyond our designs, so opening them up would be less of giving everything away and undermining our ability to remain in business.

Previously-known arguments for open source that have new weight because of the pandemic:

- Given the increased likelihood that many companies will go out of business, having open-source products can give potential customers more confidence in designing our products into their own products or curriculums. Even if Pololu were to go out of business, at least our designs could get produced somewhere else with less effort than having to design in a new product.

- Employees working on the products might be more motivated to work on them since continued existence of their creations would be less dependent on Pololu continuing to make them.

New arguments for open source specifically because of the coronavirus pandemic.

- Pololu was not particularly well set up for remote workers. While we are working on improving the situation, security and similar concerns might add more friction that would continue to make some kinds of remote work/projects impractical. If they were instead completely open-source projects independent of Pololu, security (as far as keeping designs secret) and supporting external connections to Pololu internal systems would be less of an obstacle.

- We have been soliciting donations to help Pololu survive this crisis. Potential donors might be more encouraged to donate if they had some confidence that they are supporting existence of products and designs that will continue being available even if Pololu were to stop manufacturing them.

- There are now many more people out of work (whether paid or not) around the world who might be open to donating their time and expertise to help on Pololu projects.

- There are now many more students at home or recent graduates without jobs or internships that could especially benefit from looking at or contributing to our designs.

- The pandemic has increased awareness about potential benefits of manufacturing locally, or at least being less dependent on one region or country. Perhaps that will alleviate some of the price pressure that makes it more difficult to open up designs (if you have to compete with the cheapest place in the world to make something, it’s harder to just give them your design).

In short, the heightened uncertainty about business collapses, shortage of money, and physical separation/decentralization that the coronavirus crisis is forcing on us all substantially tip the balance in favor of moving toward more open source projects in organizations like Pololu.

I would appreciate any advice or thoughts any of you have on the topic. Here a few areas you might be able to comment on:

- What do you think in general?

- I am considering specific product-based fundraising campaigns in which we could open up some existing products after exceeding some donation threshold; how does that sound?

- Are there some existing open-source projects that you would like Pololu to start contributing to or manufacturing?

- What’s the latest on open source hardware, in terms of standard licenses, business models, examples, etc? (I generally feel like I hear about open source hardware less than I did 8 years ago, and that there have been some notable disappointments/sell-outs that have dampened the movement, but perhaps I just have not been paying as much attention.)

- What are the best open-source software tools for electronic CAD and mechanical CAD?

- Are there notable recent success stories in terms of open-source physical products?

- Are there any notable examples of companies or organizations attempting to produce open-source physical products?

Thank you for your continued support, everybody! We are working hard to be worthy of it and to do our part to make things better.

Purchasing electronics components in America

|

I am a little proud (but mostly embarrassed) that I still do basically all of the electronics component purchasing for Pololu. Today I am writing about buying components because their prices have a huge impact on the end price of our products, especially when we work to cut down other costs as I have been discussing lately. Buying parts when trying to compete globally is more frustrating than you might think, and I hope that writing this will help trigger some conversations that will help us do better and also encourage component manufacturers and distributors to better support small electronics manufacturers in the United States.

I buy almost all of the electronic components that go into our products from suppliers in the United States. That includes integrated circuits, discrete semiconductor products like transistors and diodes, resistors, capacitors, inductors, and so on. The only parts I do not buy in America are components like connectors and electromechanical devices like switches and buzzers. This post is mostly about buying components in the US from US suppliers, but I will briefly touch on the non-US components to provide some background and comparison.

|

There are two main reasons for those non-US components: they are much cheaper than similar parts in the US and we can evaluate that they are good enough. That second reason is important because counterfeits and fake parts are a big problem in the electronics industry. We can look at something like a 0.1" male header or an electromagnetic buzzer and see basically what it is. Once we can be confident that a component or supplier is good enough for the level of performance and reliability we need from our products, we can look at prices to see whether it’s worth the extra hassle (and that amount of hassle keeps going down) to get the components overseas, which pretty much means China (and Taiwan, in case that distinction is meaningful). And that price difference can be huge. When I started getting connectors directly from Taiwan over ten years ago, the price difference was approaching a factor of ten, meaning that for around a thousand dollars I could buy what would cost me ten thousand domestically. Some of the price differences seem to be getting smaller, but the components still seem to be easily three to five times cheaper in China. Early on (around 2005), local salespeople would ask me what prices I was getting in China, thinking they had some better deal or connection than I knew of; nowadays, they don’t even ask or try to compete.

With all the other component types, even for the most basic parts like resistors and capacitors, we are not really qualified to evaluate them, and I would not want to be responsible for doing quality control for millions of units even if we could analyze one particular instance of a resistor or capacitor and conclude that it is good enough. So, I only buy components from reputable brands through their authorized distributors, which means I buy basically all our components through American companies (with one exception I’ll get to soon that almost doesn’t feel like an exception, anyway). Those companies also tend to be the biggest electronic parts distributors in the world.

I still buy some components from the catalog-type sources that are probably familiar even to most students and hobbyists, like Digi-Key, Mouser, and Newark. Once upon a time, these companies printed large catalogs that were the best way to find out what kinds of components even existed (especially when I was growing up in Hawaii). Digi-Key stopped printing catalogs a few years ago; Newark apparently still does. In any case, these kinds of sources now have good online resources for finding parts, they tend to have a lot of parts in stock, and they are set up for small quantities, which is why they are great resources for individuals, too. Usually, it’s very easy to buy components from these sources, and I rarely interact with anyone when I do since I usually just place the orders through the web sites at their listed prices.

|

However, the prices usually are not the best at those most convenient sources, especially when my minimum quantities tend to be full reels with thousands of parts rather than a few individual parts. So for most of my electronics purchasing, I go with big distributors like Arrow, Avnet, and Future Electronics. These companies have local offices (though for Las Vegas, “local” tends to mean in Phoenix, Arizona or somewhere in Southern California) that have salespeople that I can talk to that can help me get lower prices. Future Electronics, being a Canadian company, is the exception that I mentioned earlier; but, working with them is basically the same as working with Avnet or Arrow since they have the local staff and things like a distribution center near Memphis, Tennessee (here is a video about it).

Back when I was a student and before I started Pololu, I thought electronics distributors just bought components from manufacturers and then sold them with some markup on their cost. I think some of that did happen and still happens today, but it’s less common and less practical now because there are so many different, specialized components that they cannot all just be sitting in stock somewhere, waiting for the unlikely scenario that someone would come along and buy them. When I buy from distributors like Digi-Key and Mouser, I am almost always buying something they have in stock; when I buy from Arrow and Future, it’s almost never something they have in stock (or it’s something they have in stock because they had good reason to expect me to order).

But there was a much bigger misconception in my naive view than just the timing of when a distributor bought some parts relative to when the end customer ordered them. The major thing I learned in the early years of running Pololu is that component manufacturers charge the distributors different prices for the same components, based on the end customer! In some ways, that’s frustrating because it means I have to do a lot more work to get a good price. I have to convince each distributor and each manufacturer to give me a good price, and sometimes I have to do that with each component. It can also be a good thing in that if I do establish a good relationship with some manufacturer and distributor, the hassle per part goes down over time as they get to know our business and what factors are important to us. And some of them probably do give me a globally competitive price sometimes.

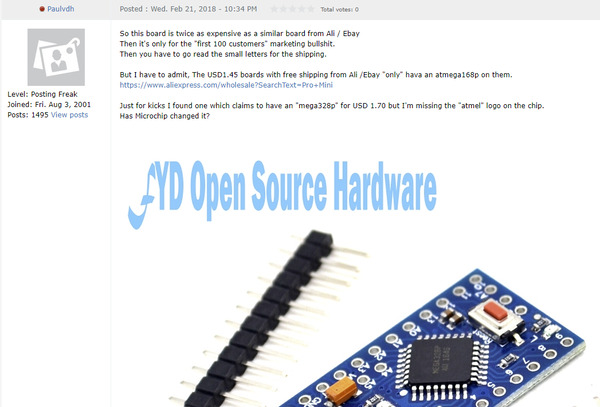

The difficulty, and what prompted me to write this post, is with those manufacturers that do not. (That or counterfeits, which is sometimes the explanation or excuse I get back from manufacturer’s representatives.) Well, the really specific thing that led me to write this post is the AVR Freaks thread about my last post, in which I introduced our new A-Star 328PB Micro:

|

AVR Freaks post about A-Star 328PB Micro announcement, the motivation for this blog post. |

|---|

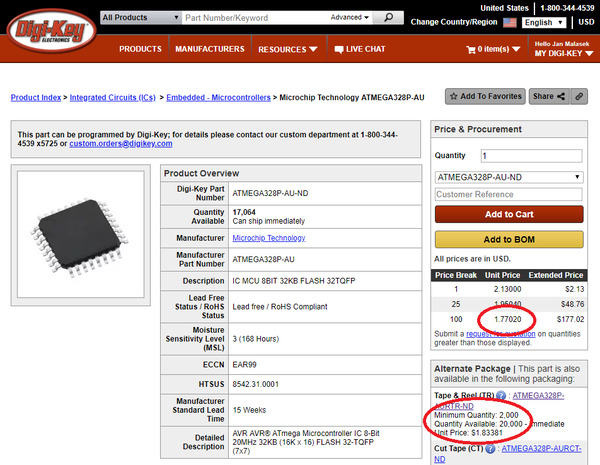

The poster mentions a board similar to Pololu’s with an ATmega328P for $1.70 (and wonders about the chip authenticity). I went to look at the part price on Digi-Key, and this is what I saw:

|

Screenshot of Digi-Key price for ATmega328P with prices highlighted, retrieved 25 February 2018. |

|---|

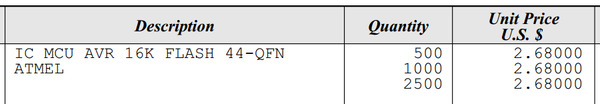

I have highlighted the relevant fields, which are the lowest prices: $1.77 each at 100 pieces, and alternately, on a reel of 2000 pieces for $1.83. 100 pieces is kind of low for a highest price break. A long time ago, I tried out the higher volume quote request option that is suggested under the 100-piece price, and after some back-and-forth, Digi-Key gave me an official volume quote for higher quantities with the exact same price as at the 100-piece break:

|

Excerpt from quantity price quote from Digi-Key (from around 2010) |

|---|

I tried it a few more times with some other parts, but it was basically the same result every time, so I have not tried special pricing with Digi-Key since. That was close to ten years ago, so maybe it’s different now, and maybe it would be different if I had asked for 10k or 100k pieces.

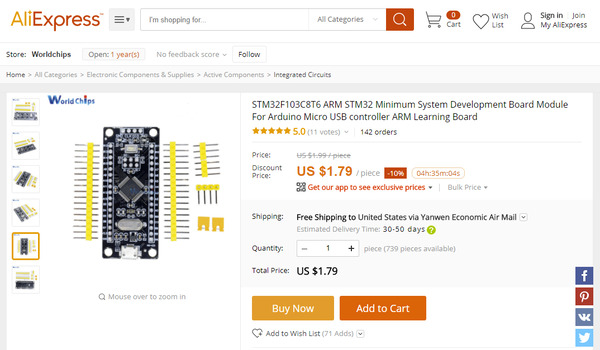

Back to the original point: you can get the whole assembled board from China, in single-piece quantities, for less than the price of just the one component, even in volume quantities. And this Atmel/Microchip example is far from atypical or anywhere near the worst case. Here is an AliExpress listing for a small development board for the STM32F103C8T6 microcontroller:

|

AliExpress listing for an STM32F103 development board for $1.79 including shipping, captured 25 February 2018. |

|---|

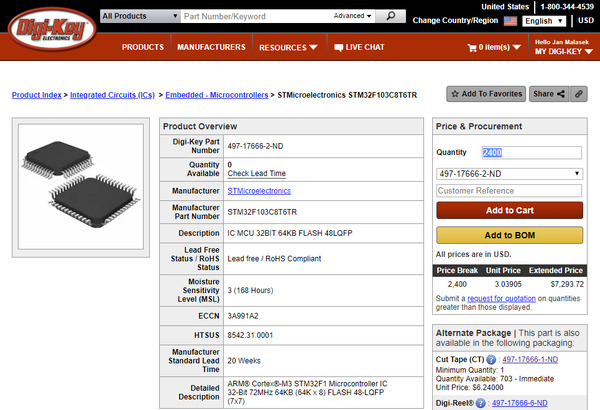

In this case, Digi-Key has prices listed for higher quantities than in the earlier example, and the 2400-piece reel has the best unit price of $3.04:

|

Screenshot of Digi-Key price for STM32F103C8T6, retrieved 25 February 2018. |

|---|

I have been working on pricing for similar STM32 parts, and even at twenty thousand pieces (not through Digi-Key), they are not getting to the prices of just one of these complete boards, with double-sided assembly and a bunch of additional components (and free shipping!—though that is some separate scam that I do not blame the electronics component manufacturers and distributors for). Something clearly doesn’t add up, right?

|

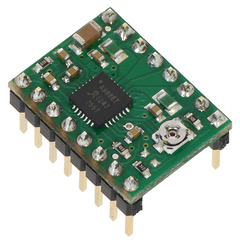

As I mentioned earlier, some manufacturers will say the parts in the cheap boards from China are counterfeits. I believe that is the explanation in some cases, and we have our share of frustrations with knock-offs and counterfeits of our own products. But I had one experience around five years ago that makes me very skeptical that that is anywhere near the whole story. One of our more successful early products, at least by number of units sold, was a basic carrier for Allegro’s A4988 stepper motor driver. I remember being frustrated because Allegro seemed to have some deal in place with Digi-Key that gave them the best prices (and unlike the examples above, Digi-Key did have volume breaks up to many tens of thousands on that part). Digi-Key has been getting better on prices, but still, paying “Digi-Key prices” seemed like an insult when I was buying tens of thousands of these parts at a time.

It became more of a problem when the knock-offs of our boards started appearing on eBay and other sites for basically the same prices as just our component costs. I kept trying to get my suppliers to help me with my prices until I got the parts from Asia via Future Electronics. They assured me these were genuine parts through their global partners or subsidiaries, and they could do that for me because they were not authorized distributors for Allegro in the United States. So, that alone was a good indication that these parts were out there, through reputable sources, at lower prices than I could get in the US. But the conclusion to this story gets better: someone who could do something about it at Allegro finally got word that I was getting these parts elsewhere (they noticed the sales abruptly went away, and they wanted to see my invoices from other vendors) and reduced my authorized price, through Arrow, to almost half of what it had been.

This was over the course of maybe two years, and while it did help and we lowered our prices, I believe we missed out on a lot of potential sales because it took so long to get the prices down. The sad thing is that there are probably many more missed opportunities, not even just for Pololu, because of how components get priced in the US. The manufacturers seem more willing to cut prices after demand is proven and they start losing sales rather than up front to make the sales happen in the first place. And to be clear, I am not talking about small quantities like broken reels and cut tape that require extra handling and processing. I also understand that these modern 32-bit microcontrollers like the STM32 are such amazing achievements that it seems really unappreciative to complain about one costing $2. It’s just that when the same parts are costing one dollar somewhere else, we need to figure out how to get that price if we want to be globally competitive with our products.

Since I know many of you are also interested in open-source hardware, I should mention the ramifications component pricing has for openness with our designs. One of the factors that goes into how much information we release is how good I think our component price is. It’s easier to share key components that we use if I think we can keep making our products competitively.

Back to some of the comments that led me to start writing on this topic. I hope I have shown you a different kind of behind-the-scenes view than just the machines that go into making our products. Some of that “twice as expensive as a similar board from Ali / Ebay” goes all the way down to the basic component level. I hope you can see that I am working on addressing that. I would be interested in what other small manufacturers in America (and in other countries besides China) do. Should I just start sourcing more components from China? Should I be using smaller distributors in the US? (I am skeptical that would make a big difference because of my understanding that manufacturers are basically setting the prices). Or is there something else I’m completely missing? I know some of you who read my posts work for the electronics manufacturers and distributors; can you help push for getting better component pricing in the US? For all of you who like making electronics, wouldn’t it be nice to have the option (or for your kids to have the option) to do that without having to live in China or being limited to industries like aerospace and military where components costs might not matter as much?

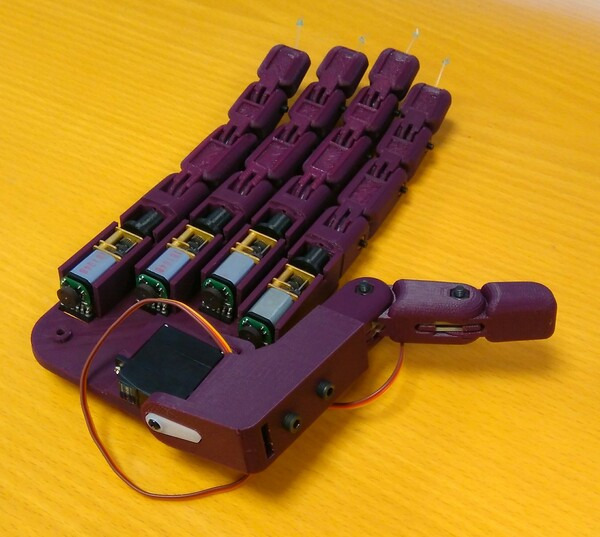

Open-source myoelectric hand prosthesis

Pololu customer Alvaro Villoslada made this impressive open-source 3D-printable hand prothesis. Each finger uses a 1000:1 Micro Metal Gearmotor HP 6V with Extended Motor Shaft to wind a fishing line—acting as a tendon—onto a spool. A magnetic encoder attached to each motor enables closed-loop control, and the motors are driven by DRV8838 DC motor driver carriers. An RC hobby servo controls the thumb position. Alvaro uses a Teensy 3.1 microcontroller to monitor the encoders and control the actuators, and he built a user interface in Python for controlling the hand from a computer.

|

For CAD files, detailed instructions and more pictures and videos, see the Hackaday project page.

Apeiros robot Kickstarter

|

Abe Howell posted to our forum about a Kickstarter campaign for a robot he calls Apeiros. It is an open-source robot he designed as a teaching tool for STEM. Apeiros uses some of our parts and our laser cutting service in its construction. It is also designed to be upgraded with some of our sensors like the QTR-3 or QTR-8 reflectance sensor arrays or the Sharp GP2Y0D810Z0F Digital Distance Sensor. Some of the higher pledge rewards on the Kickstarter include these sensors. You can learn more about the robot on its Kickstarter page.

Not your average alarm clock!

Leonid Karchevsky, of Xronos Clock, used our Custom Laser Cutting Service to create an enclosure for his Arduino Based Talking Alarm Clock, the Xronos Clock. The Xronos Clock is open-source, hackable, customizable, and is available in both assembled and kit form.

|

|

|

More fun machines for us, better quality and lower prices for you

As we head into what is traditionally a week of heavy discounting, I want to give a little update about some new equipment that will be a foundation for our long-term commitment both to lowering prices and increasing the quality and sophistication of our products. Plus, I figure these kinds of machines are fun for our customers to look at. Continued…

Thoughts on Open-Source Hardware

As open-source hardware (OSHW) has become more prominent over the past five years or so, I have heard questions about where I or Pololu stand on the subject. Most recently, I got into a bit of a discussion with Phillip Torrone of Make and Adafruit on one of his blog posts, and his questions and subsequent interview pushed me to try to organize some of my thoughts about OSHW. Because there are many aspects to OSHW, I don’t have a simple conclusion like, “It’s great!” or “It’s the future!” or “Pololu will never release an OSHW product.”. I am skeptical of some of the claims by OSHW proponents and of the significance of the more organized aspects of the OSHW movement. However, what is going on is very significant to me because it affects Pololu’s business and involves issues I care about a lot, such as freedom, creating things, and education. Continued…

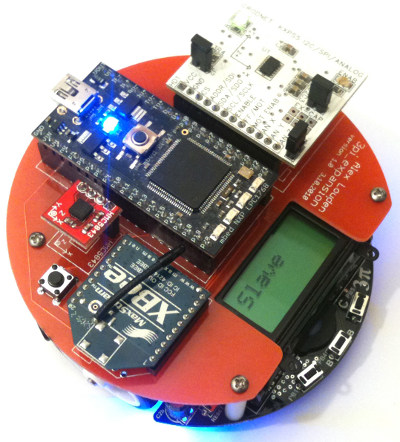

3pi PCB skeleton

|

Alex Louden has released an open-source template for custom 3pi expansion boards for use with the Eagle PCB design software. The picture shows an example expansion with an mbed microcontroller, Xbee, and accelerometers.

Featured link: http://alexlouden.com/2010/3pi-pcb-skeleton/